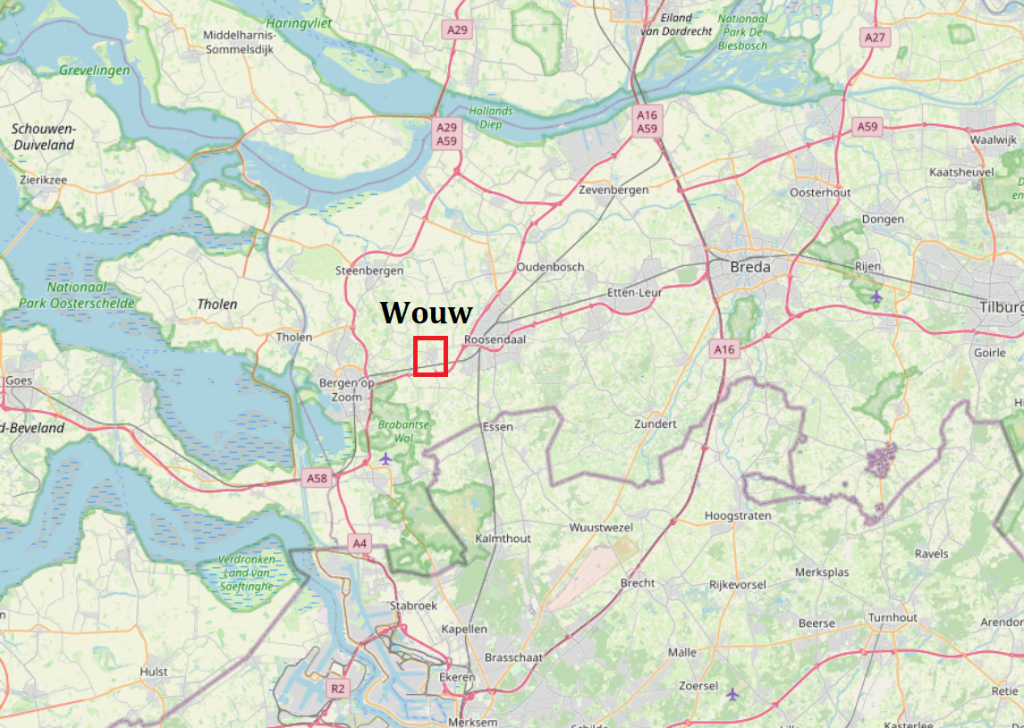

This blogpost is about Ymme die Lems, the female matriarch of a farming family in the 15th century seigneury of Woude (present-day Wouw, Netherlands). I encountered her multiple times in my research into the settlement history of the northwestern corner of Dutch Brabant so here I put together what I know about her. This case study serves to show what information can be gleaned from a medieval tax register about a medieval commoner in a rural community.

Spelrestrate

Ymme owned land in “Spelrestraete” a medieval street hamlet consisting of a spread out cluster of farms located along a hay-road that originally led from the village of Woude to Spelreborch, a by then obsolete manorial court, near present-day Steenbergen. The houses near the old main road towards Roosendaal were known as “Spelrestrate aen tfelt” and the houses further north where the soil was more peaty as “Spelrestrate in tven“. In the late 15th century, the hamlet comprised around 22 farmhouses, a number which stayed stable untill the late modern period.[1]

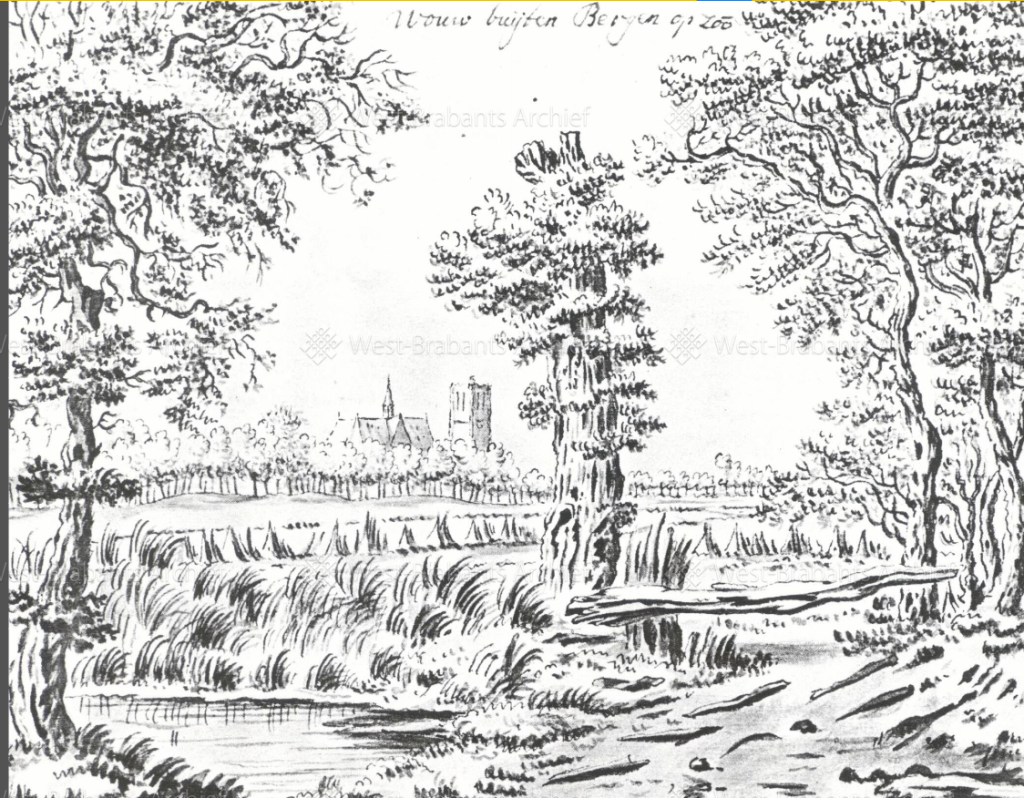

This hamlet of Spelrestraete (just like the neighboring community of the Triest-homestead) was a satellite hamlet of Woude, the head town where the parish church was situated. As its own seigneury, Woude maintained a local law court with baillif, aldermen and a local militia. Furthermore, it was protected by a moated castle which was used by the lord of Bergen op Zoom as his personal residence.

Ymme die Lems

Ymme is mentioned in the seigneurial tax register of Bergen op Zoom of 1424 (ARR BoZ inv. 1338). It is in these kinds of sources that we find the average medieval commoners: the smith, the miller, the butcher and also Ymme herself.

In the register of 1424, she is identified as Ymme die Lems (daughter of Lems) or Ymme Lem Dierwyen dochter (daughter of Lem and Dierwye). She married a farmer called Adde van den Dale. She and her husband belonged to the tax post of Spelrestraete, so presumably that’s where they lived.

The family of her husband Adde came from the farms located in the Vroenhout dale which is the geographical depression between Spelrestraete and the street settlement of Vroedenhout (present-day Vroenhout). The father of Adde was a tenant farmer called Arnout and can be found paying rent to Pieter Noriiszone in the tax register of 1359.

The hamlets of Vroedenhout and Spelrestraete are within half an hour walking distance and according to 15th and 16th century accounts often paid their taxes and tithes together. Both peasant communities had access to a local chapel where occasionally masses were held. As mentioned before, the parish church was located in the village of Woude, so for some religious festivities and church services they had to walk to Woude.

Perhaps that Ymme and Adde met each other at such an occassion. Together they had six children: Claes, Jan, Arent, Godscalc, Willem and Roelant. The children owned land both to the west of Spelrestraete, in the area called “opte donck” and to the east, near Vroedenhout, in an area called “die cauwe“.

Female prominence

Why did Ymme stand out to me? Well, for two reasons: 1) she was taxed for land separate from that of her husband. This is not very common (only 10% of the tax posts concern women). Here it is important to remember that medieval inheritance law did allow for women to inherit land.

2) many of her sons are identified in the register as “X son of Ymme” instead of “X son of Adde”. In total, her name is mentioned over a dozen times, mainly as a parentage identifier for her six sons.

This seems to suggest that the tax collector who visited the hamlet, encountered a community to which Ymme die Lems had a lot of significance; at least more so than her husband because her name occurs more often.

Also interesting is that Ymme paid 8 Flemish pennies of tax to the lord of Bergen op Zoom whereas her husband Adde paid 7 pennies. Presumably because she owned more land. Of course, it would be interesting if we could identify the plots which Ymme owned, but this seems not to be possible.

The tax register of 1424 only refers to the taxable plots by the name of the farmer and the amount of tax that was due. The boundaries of the plot are not provided in the register and only occassionally the measurements of the plot are mentioned. As a consequence, only in the rarest of cases can a medieval plot be identified, either by its name or by its measurements.

We might however have a clue as to where Ymme’s farm was located. As mentioned before, most of her sons seem to own land in the area called “opte Donck“. This was an old unenclosed open field area that is located to the west of Spelrestrate. It might therefore be attractive to place the homestead of Ymme die Lems on the Spelrestraete road at the closest point to the fields of the “Donken” arable complex. However, without more identifiable fields that we can link to her taxable possessions, such a suggestion remains speculative.

Conclusion

I hope that this case of a Brabantine female farmer, who lived almost 600 years ago, shows that some interesting nuggets of information about medieval female commoners can be found in the tax registers. And however faint the traces of the life of Ymme die Lems are, it seems clear that she was a significant figure in the fifteenth-century rural community in which she lived.

Endnotes

[1] see Van Ham (1979:316) who tallied all the houses mentioned in the late 15th c. seigneurial tax register of Woude AAR BoZ inv. 1342 and compare with the tally in Delahaye (1980: 239).

Bibliografie

AAR BoZ inv. 1338, Legger van cijnsplichtige personen of van in cijns uitgegeven percelen van Wouw, met de gehuchten onder Roosendaal, Kruisland en Langendijk, 15e eeuw (dated to 1424 in Kerkhof 2020a)

Delahaye, A. (1980). “III. Wouw in vogelvlucht tussen 1570 en 1813”. In: A. Delahaye, W.A. Van Ham en J.H.F. Bos (eds.), Woide…die Wouda; opstellen over de geschiedenis van Wouw, 153-264.

Van Ham, W.A. (1979). ‘Dorp en dorpsleven in middeleeuws Wouw’. In: De Heren XVII van Nassau Brabant; publikaties van het archivariaat “Nassau-Brabant”, 315-336.

(nog te verschijnen) Kerkhof, P.A. (2020a). “Saer, Saert; een Zuid-Nederlandse veldnaam van oznekere oorsprong.” Noordbrabants Historisch Jaarboek.

Kerkhof, P.A. (2020b). “De veldkapellen in de parochie Wouw en het schepenprotocol van 1507-1511”. Heemkundekring de Vierschaer Wouw jaargang 38-3, 4-12.

2 gedachtes over “Meeting a Brabantine female farmer”